PBM-5 Mariner

Martin PBM-5 Mariner

The History of the PBM-5 started way back with a man that had started the Glenn L. Martin Company in 1911, Glenn Martin. Best known for his bombers, Martin was contracted to build an improved flying boat for the Navy in 1937.

Martin started work on a new and improved military flying boat in 1937. The Consolidated PBY Catalina had been doing well and the Navy wanted a machine superior to that. Martin came up with the Model 162. On June 30, 1937 Martin was awarded the contract to build a prototype of the 162, designated XPBM-1 (Experimental Patrol Bomber Martin 1). With test flights commencing, the Navy placed an order for 20 aircraft designated PBM-1 on December 18, 1937. With a revised tail design, the PBM-1’s were completed and delivered by April 1941 with the name “Mariner”.

In the fall of 1940 the Navy ordered 379 improved Model 162B’s (PBM-3’s) and Martin’s plant was given another location courtesy the US Government. The PBM-3 was similar to the PBM-1, but the 3’s had upgraded engines, larger wing floats, bigger bomb bays, powered nose, dorsal, and tail turrets, and revised beam gun positions. Later the 3’s were upgraded from a 3-bladed propeller, to a 4-blade.

There were also PBM-3R’s constructed in 1942 serving the Naval Air Transport Service. Following that model there was the, XPBM-3E, PBM-3B, PBM-3C, PBM-3S, and PBM-3D. A PBM-4 series was discussed due to inadequate engine power in the past PBM’s, but due to a limited supply of the R-3350 engines, the idea was scrapped.

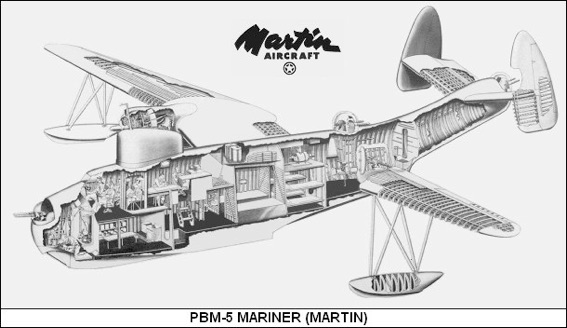

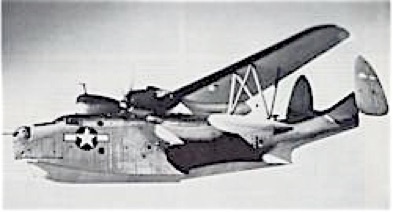

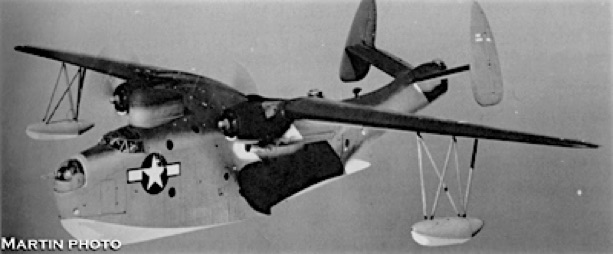

With the new Pratt & Whitney R-2800-34 Twin Wasp (2,100 horsepower each), the PBM-5 was ordered and deliveries started in August of 1944. The PBM-5 configuration was similar to the PBM-3D, but the 5’s were fitted with (initially) 3-blade Hamilton Standard props, but later changed to 4-blade Curtiss Props, and in addition the 5’s were fitted with jet assisted take-off. The wing span was a massive 118 feet, the length of the PBM-5 is, 79 feet, 10 inches, and height, 24 feet, 10 inches. Its rate of climb was 590 feet per minute at 9,500 with a max. speed of 178 knots.

It had two .50 caliber guns on the nose turret and two .50 caliber guns on the tail turret. Its maximum bomb load was recorded at 12,000 lbs.

Included in the 1944 order was the PBM-5 (bureau number 59172) that is now at the bottom of Lake Washington in 65 feet of water down at the south end.

After WWII and the cold war era, #59172 was stationed at Naval Air Station Seattle, Washington. Its last operational assignment was in late 1948.

On May 6, 1949 the PBM-5 took off from NAS Seattle heading for the Boeing seaplane ramp where it was to be put in storage. Lt. Ralph Frame made a clean take-off and landing but due to winds missed a tie-up buoy while taxiing to shore. There was a small pier sticking out of the water, and unable to turn around or maneuver very well, Frame struck the piling with the starboard wing pontoon. The wing pontoons kept the plane even while on the water and with one inoperable the plane listed, then turned on its side.

Knowing what was going to happen next, Lt. Frame and his 6 other crew-members escaped into the cold lake unhurt. When the plane reached the bottom it had totally flipped upside-down.

SALVAGE ATTEMPTS

In 1980 and 1981 over one hundred artifacts were removed from the plane and given to the National Museum of Naval Aviation at Naval Air Station, Pensacola Florida. Additional artifacts were suspected to have been pilfered over the next 20 years, given that the wreck is in recreational scuba limits.

In 1990, Navy Supervisor of Salvage and Naval Reserve Mobile Diving Salvage Unit One Detachment 522 (NRMDSU-1DET 522) attempted to salvage the aircraft. They proceeded to conduct training exercises, and worked to remove the overbearing silt, pushed from the Cedar River outflow that covered a lot of the wreck. It was this attempt that a Detachment 522 diver, Ted Gunhus, died of a pre-existing heart condition while working on the PBM. The project was halted after this incident.

According to the Naval Historic Center, the next 6 years included dives and plan formulating to recover the wreck. It was reported that the non-profit group Mariner/Marlin Association with the help of Mobile Diving Salvage Unit One, the Chief of Naval Operations and the Naval Historical Center along with several other supporters, would spearhead the recovery.

At the same time, Bob Mester was seeking salvage rights to the abandoned plane. From a Seattle Times report on September 6, 1996 Mester stated, “The Navy has abandoned this plane. It’s not listed on the Navy inventory and its logbooks have been destroyed.” Bob got a state permit to salvage the wreck in 1991, but due to the Navy’s continued insistence that they still owned the wreck and were going to salvage it themselves, the permit ran out while waiting on a ruling from the US District Court for ownership in his name.

The Navy did try to salvage the flying boat, but failed. They decided to try and raise the gigantic plane out of the mud by the tail. With the suction along with the overall weight, and tension putting strain on only the tail section, the whole tail ripped off and the plane once again settled to the bottom. The tail section was brought to the surface anyway, loaded on a barge, and reportedly turned over to the National Museum of Naval Aviation for a restoration project.

After this last attempt, and one diver getting a case of DCS, the Navy abandoned the project.

It still lies there today, upside-down in 65 feet of water.

-

-Home

Below: Video shot by Frog Kick Diving (PBM Footage starts at 2:23)

Below footage courtesy Jared Jensen