Tacoma Narrows Bridge

Tacoma Narrows Bridge

(Galloping Gertie)

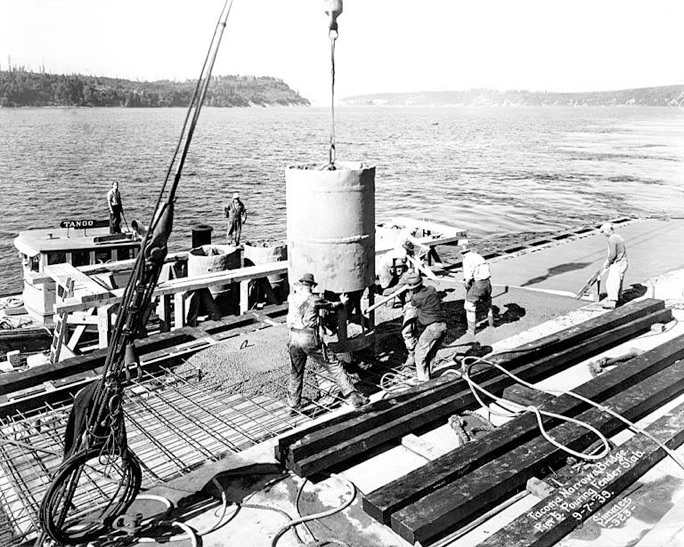

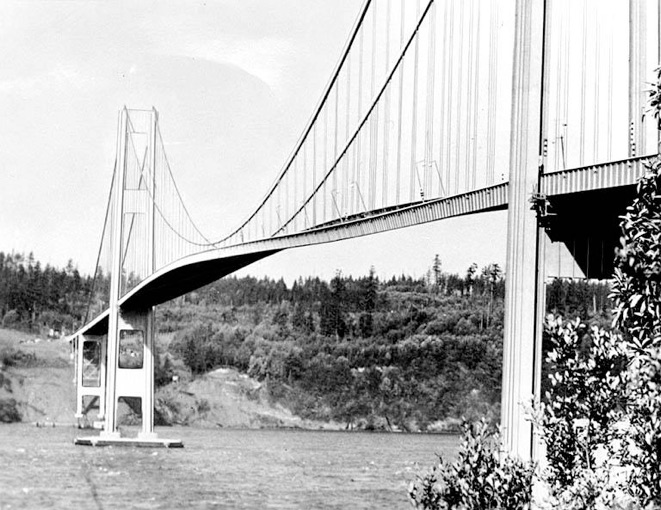

The Tacoma Narrows Bridge, the portal for economic and military expansion to the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State, was built between November 1938 and July 1, 1940.

The Pacific Bridge Company submitted the lowest bid for the building of the Narrows Bridge in the amount of $5,594,730.40. The amended designs from the compromising Clark Eldridge and Leon Moisseiff were taken into account and were approved by the Public Works Administration.

During construction of what would be known as the 3rd longest suspension bridge in the world, workers dubbed the bridge Galloping Gertie. Winds through the Narrows can blow at a fierce and steady rate. At times the laborers were in awe of the wavelike motion the bridge span would generate in the gust. “Imagine driving in an earthquake,” is how some described it. There were several accounts of “seasickness” while driving over the unsettling Gertie.

The bridge opened on July 1, 1940. Tolls were charged to commuters and travelers alike to pay for the construction bonds. Unfortunately the tolls were more expensive then the eliminated ferry service; $.75 one way and $.10 for pedestrians. On opening day though, over 2,000 vehicles crossed the bridge, with regular crossings averaging at 1,661 vehicles a day.

With the span continuing to rise and fall like a ribbon in the wind, engineers were hired to address the extreme problem. Professor F.B. Farquharson of the University of Washington, along with other engineers worked diligently with scale models to recondition the existing viaduct, but the solution thwarted the men.

For approximately four months the commuters endured the attack of their senses whenever there was a slight breeze, but in the morning of November 7th, 1940 the winds picked up through the narrows to a blistering 42 miles an hour. The bridge could handle no more.

The bridge deck started out at a “normal” 3-5 feet on the morning of the 7th, but by late morning, with each arc building momentum, the twisting motion grew stronger. The span movement had gone from 3-5 foot to 28 foot undulations. This extreme ribbon effect caused the road to tilt 45 degrees from horizontal in each direction.

"Just as I drove past the towers, the bridge began to sway violently from side to side. Before I realized it, the tilt became so violent that I lost control of the car... I jammed on the brakes and got out, only to be thrown onto my face against the curb.” Leonard Coatsworth the last driver on Galloping Gertie, reports on his last attempt to cross the bridge. Warned by the toll booth operator that the bridge “is a little shaky” he attempted the crossing. With his daughter's black cocker spaniel Tubby in the car with him, he proceeded through the first towers. The bridge at that point was rippling so badly Mr. Coatsworth decided to halt the car and make a run for it.

"Around me I could hear concrete cracking. I started to get my dog Tubby, but was thrown again before I could reach the car. The car itself began to slide from side to side of the roadway.”

Without his daughter’s precious pet, Coatsworth crawled on his hands and knees, till they were bleeding and raw, for about 500 yards death gripping the curb as he went. Making it safely back to the toll plaza, Leonard watched with hundreds of other spectators the bridge start to tear apart.

The bridge held together for about 30 minutes from when the twisting began and at 10:30 AM, a center span floor panel dropped into the frigid waters 195 feet below. This set the imminent destruction in motion; various sections of the road bed continued raining into the swift Narrows. At 11:02 AM 600 feet of the western end of the bridge twisted and flipped, and snapped free of the grasping stanchion, then plummeted down into the Sound. The discouraged but hopeful engineers at the scene watched this last episode and believed that the bridge would settle down since this large section of roadway was gone, but they were very wrong. At 11:09 AM, the remaining bridge sections tore free from their supports and plundered to the dark depths below. When this last violent break happened, the 1,100 foot side spans dropped 60 feet, and like a rubber band, bounced back up and settled into a sag of 30 feet. As for the whole mid span, it now rests in the depths of the Narrows from 160 feet to 240 feet deep.

Noted in the history books as one of the largest bridge disasters of the world with the only victim being a small dog named Tubby, I wonder how this resonated with the little girl who lost her beloved pet in this historical display of faulted human ingenuity.

“…Safely back at the toll plaza, I saw the bridge in its final collapse and saw my car plunge into the Narrows… With real tragedy, disaster and blasted dreams all around me, I believe that right at this minute what appalls me most is that within a few hours I must tell my daughter that her dog is dead, when I might have saved him." Leonard Coatsworth

The aftermath

The news of Galloping Gertie's demise on November 7, 1940 startled Hallett R. French. The 45-year old Seattle-based insurance agent for Merchants' Fire Assurance Company of New York, had written a $800,000 policy on the bridge for the State. French believed there was no chance of the bridge collapsing. So, being a rather inept criminal, French deposited the $70,000 in premiums in his bank account without reporting the transaction to his firm. He was vacationing in Idaho when he got word on November 8 that all was not right at the Narrows.

On December 2, 1940 Seattle police arrested French for grand larceny. French was denied bail and his trial set for the first of February 1941. French returned some $17,500 of the missing funds. His businessmen friends in Seattle begged the court for leniency on French's behalf. On February 7th, Hallett French got a version of Galloping Gertie's revenge. "Guilty," he pleaded, and the judge promptly sentenced French to 15 years in the State Penitentiary in Walla Walla.

French did have one bit of good luck. He served only two years, then was released for "good behavior." He soon found a job at a shipyard in Seattle. Then, the newspapers stopped caring about his career. From WSDOT website

Eyewitness accounts

Clark Eldridge

Project Engineer, WA State Toll Bridge Authority

"It was my bridge."

"I was in my office about a mile away, when word came that the bridge was in trouble. At about 10 o'clock Mr. Walter Miles called from his office to come and look at the bridge, that it was about to go.

"The center span was swaying wildly, it being possible first to see the entire bottom side as it swung into a semi-vertical position and then the entire roadway.

"I observed that all traffic had been stopped and that several people were coming off the bridge from the easterly side span. I walked to tower No. 5 and out onto the main span to about the quarter point observing conditions. The main span was rolling wildly. The deck was tipping from the horizontal to an angle approaching forty-five degrees. The entire main span appeared to be twisting about a neutral point at the center of the span in somewhat the manner of a corkscrew."

"At tower No. 5, I met Professor Farquharson, who had his camera set up and was taking pictures. We remained there a few minutes and then decided to return to the east anchorage warning people who were approaching to get off of the span.

"At that time, it appeared that should the wind die down, the span would perhaps come to rest and I resolved that we would immediately proceed to install a system of cables from the piers to the roadway levelin the main span to prevent any recurrence...."

"I was then informed that a panel of laterals in the center of the span had dropped out and a section of concrete slab had fallen. I immediately went to the south side of the view plaza. The bridge was still rolling badly. I returned to the toll plaza and from there observed the first section of steel fall out of the center. From then on successive sections towards each tower rapidly fell out."

In his 1986 unpublished memoir, Eldridge wrote,"I go over the Tacoma bridge frequently and always with an ache in my heart. It was my bridge."

F.B. "Bert" Farquharson

Professor of Engineering, University of Washington

"I thought she would be able to fight it out"

"I was the only person on the Narrows Bridge when it collapsed. When I arrived at about a quarter to ten o'clock, the bridge was moving in the familiar rippling motion we were studying and seeking to correct.

"About a half hour later, it started a lateral twisting motion, in addition to the vertical wave. It had never done that before.

"At least six lamp posts were snapped off while I watched. A few minutes later, I saw a side girder bulge out. But, though the bridge was bucking up at an angle of 45 degrees, I thought she would be able to fight it out. But, that wasn't to be.

"I saw the suspenders (vertical cables) snap off and a whole section caved in. The bridge dropped from under me. I fell and broke one of my cameras. The portion where I was had dropped 30 feet when the tension was released.

"I kneeled on the roadway and stayed to complete the picture."

Winfield Brown

Twenty-five year old college student Winfield Brown decided to walk onto Gertie shortly before 10 a.m. that morning. "I decided I'd like to get a little fun out of it," he later said. So, he paid the 10-cent toll and strolled onto the rolling bridge.

"After walking to the tower on the other side and back, I decided to cross again. It was swaying quite a bit. About the time I got to the center, the wind seemed to start blowing harder, all of a sudden. I was thrown flat. A car came up about that time. The driver got out, walking and crawling on the other side. We didn't have time for any conversation."

"Time after time I was thrown completely over the railing. When I tried to get up, I was knocked flat again. Chunks of concrete were breaking up and rolling around. The knees were torn out of my pants, and my knees were cut and torn."

"I don't know how long it took to get back. It seemed like a lifetime. During the worst parts, the bridge turned so far that I could see the Coast Guard boat in the water beneath."

"As soon as I got off the bridge, I became sick. So, I went to the home of a cousin and laid down for a while. I've been on plenty of roller coasters, but the worst was nothing compared to this."

"When I got back, I remembered the bridge man [toll collector] had said something about a dime each way. I mentioned it to him.

"He said, 'Skip it'."

Leonard Coatsworth

News editor, Tacoma News Tribune

"I saw the Narrows bridge die today, and only by the grace of God, escaped dying with it. . . .

"I drove on the bridge and started across. In the car with me was my daughter's cocker spaniel, Tubby. The car was loaded with equipment from my beach home at Arletta.

"Just as I drove past the towers, the bridge began to sway violently from side to side. Before I realized it, the tilt became so violent that I lost control of the car. . . . I jammed on the brakes and got out, only to be thrown onto my face against the curb."

"Around me I could hear concrete cracking. I started back to the car to get the dog, but was thrown before I could reach it. The car itself began to slide from side to side on the roadway. I decided the bridge was breaking up and my only hope was to get back to shore."

"On hands and knees most of the time, I crawled 500 yards or more to the towers . . . . My breath was coming in gasps; my knees were raw and bleeding, my hands bruised and swollen from gripping the concrete curb . . . . Toward the last, I risked rising to my feet and running a few yards at a time . . . . Safely back at the toll plaza, I saw the bridge in its final collapse and saw my car plunge into the Narrows."

"I saw Clark Eldridge (Toll Bridge Authority engineer), his face white as paper. If I feel badly, I thought, how must he feel?"

"With real tragedy, disaster and blasted dreams all around me, I believe that right at this minute what appalls me most is that within a few hours I must tell my daughter that her dog is dead, when I might have saved him."

Ruby Jacox

Several minutes before Leonard Coatsworth drove onto the Narrows Bridge, the next-to-last vehicle on the rolling span was a delivery truck owned by the Rapid Transfer Company. Inside were business partners Ruby Jacox and Arthur Hagen. The toll taker warned them that the bridge was "a little shaky."

" All of a sudden the bridge began to rock. We were afraid the truck would turn over, so we ... jumped out. We could only crawl on or hands and knees and got about 10 feet away when the truck fell over."

"We crawled along hanging onto the ridge of the center of the roadway. Just to keep our courage up we never stopped talking. Chunks of the concrete actually burst out of the bridge deck as it swayed, groaned and buckled. I fell dozens of times on the pavement."

"I was ready to give up, but he (Mr. Hagen) just dragged me along by the shoulder. One of the lampposts just did miss my head. Sometimes I was sure we'd never get off the bridge."

"I kept thinking that this bridge was something that couldn't break. It had been inspected by government engineers. And experts had planned it so it would stand any strain."

Unsung heroes came to their rescue. When the wind subsided and Gertie calmed her twisting and swaying for a short time, two workmen for the bridge's painting contractor backed their truck onto the span, hauled the weary couple aboard and drove safely to the west end. Ruby Jacox suffered painful bruises on her knees, left hip and ankles. She spent the night in a hospital recovering from "terrific nervous shock."

Howard Clifford

Photographer, Tacoma News Tribune

"I was on the Narrows Bridge when it broke in the middle and ... I hope that I never again go through such a nerve racking experience."

"The regular photographer was out on assignment. I was the back up, and they told me to grab a camera and go out there. But, they said, don't take any risks under any circumstances. I grabbed the only camera, an old Graflex, a large and cumbersome 4x5 reflex camera that you hold against your stomach and look down into the viewfinder."

"When I arrived, the bridge had literally run amok, bouncing and twisting like a roller coaster. Working my way up to the tower with the greatest difficulty, I shot a few more films. Suddenly, the bridge seemed to sway and lurch more than ever, and I began shooting as fast as I could."

Clifford decided to walk onto the center span to try to save the dog, Tubby, in Leonard Coatsworth's car.

"I probably wouldn't have gone out there, if it hadn't been for the dog. I liked dogs and had seen the Coatsworth's dog at a company picnic recently. Or, if I didn't have the camera, I probably wouldn't have gone out on the bridge. I got about 10 yards from the tower and stopped."

"Taking another squint into the camera viewfinder, I saw the span buckle and start to break in the center. I pressed the camera trigger and started to run."

"I tried to run up the yellow line in the center of the roadway, but found myself being bounced from one curb to the other and making no headway towards shore. I felt I could be tossed over the edge at any time. I was running in the air part of the time, because the bridge was moving faster than gravity. It dropped out from under me and then bounced back, knocking me down to my knees, banging the camera on the pavement."

"Behind me I heard rumblings and explosive sounds which scared the daylights out of me. Having played football during my junior high and high school days, I tucked my camera under my arm and charging low got that added ounce of energy from somewhere which enabled me to make some headway toward the bridge entrance."

"I was half-running, half-crawling. In a few minutes, which seemed like hours, I was up with my fellow photographer [Barney Elliott of the Camera Shop], who had got a considerable start, and we both made our way to the toll gate office, exhausted, but oh so thankful."

"Returning to the Tribune office, . . . within a very short time I was transmitting photos of the collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge to the entire world. It was only then that I noted that my trousers were torn and my knees resembled raw hamburger. The next morning I looked even worse. I was bruised, black and blue from my hips to my feet the next day and for two weeks."

"I don't think anything more exciting has ever happened to me." From WSDOT website

Documentary

For a local full length documentary on the Tacoma Narrows Bridge contact Bob Mester at: robert.mester@comcast.net

-

-Home

November 7, 1940 Photo by Jim Bashford, Courtesy UW Special Collections

Courtesy Alex Pasternack

Footage from the Prelinger Archive and The Camera Shop. Music by Tim Hecker.

He put the video together for this story > http://motherboard.vice.com/read/the-myth-of-galloping-gertie